by Liz Stevens, writer, Plastics Business

As 2021 comes to a close, plastics manufacturers are facing enormous pressures. An increased demand for their products is crashing head-on into the lingering worker shortage and a relatively new but crippling resin supply chain crunch. Processors have struggled for some time to find trained workers during a period when fewer workers than ever are seeking manufacturing jobs. Add to that the current very tight resin supply, the rising prices for resin stock and shipping fees – and a booming market for products – it is no surprise that processors are lying awake at night, wondering how to meet this trio of challenges.

To offer manufacturers advice and resources to tackle the resin supply quotient of this difficult situation, Plastics Business spoke with Bruce Flannery, product director-commodities at Amco Polymers, an Orlando, Florida, player in resin distribution; Louis Columbus, senior industry marketing manager at the ERP, MES and CAD/CAM software company DELMIAWorks (formerly IQMS) of Paso Robles, California; and Jenny Christensen, VP of marketing at BinMaster, Lincoln, Nebraska, which offers digital resin bin level sensors and the ResinView® web application for resin inventory management. We asked Flannery, Columbus and Christensen how the resin supply jam transpired, what the resin supply forecast looks like for the near future, and for their best advice on what manufacturers can do to stay on top of resin inventories and minimize supply chain disruption.

How Did This Supply Chain Jam Come About?

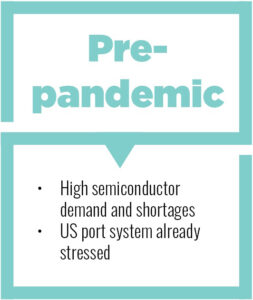

The current resin supply chain quagmire came about due to a number of factors. Prices for imported resins had already risen in 2018 due to the Trump administration’s trade and tariff wars. Then COVID-19 hit, sending shock waves that resulted in factory slowdowns or shutdowns beginning in China and eventually spreading to the US. BinMaster’s Christensen explained how the pandemic affected BinMaster’s parent company, Garner Industries, a plastics manufacturer. “When COVID-19 started, Garner Industries was considered an essential business because of what we make at our plant, such as plastic

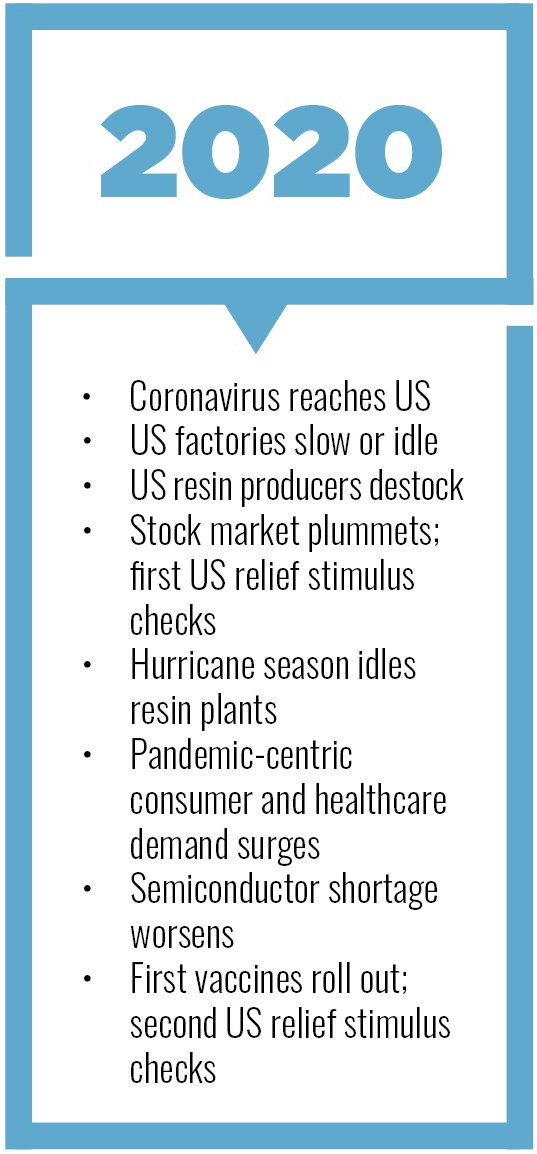

The current resin supply chain quagmire came about due to a number of factors. Prices for imported resins had already risen in 2018 due to the Trump administration’s trade and tariff wars. Then COVID-19 hit, sending shock waves that resulted in factory slowdowns or shutdowns beginning in China and eventually spreading to the US. BinMaster’s Christensen explained how the pandemic affected BinMaster’s parent company, Garner Industries, a plastics manufacturer. “When COVID-19 started, Garner Industries was considered an essential business because of what we make at our plant, such as plastic  injection molded parts for PPE equipment, plastic packaging components for sanitizers and chemicals, and instrumentation used in the food industry,” she said. “Our operation never shut down, so we weren’t impacted as much as other companies that had extensive shutdowns.”

injection molded parts for PPE equipment, plastic packaging components for sanitizers and chemicals, and instrumentation used in the food industry,” she said. “Our operation never shut down, so we weren’t impacted as much as other companies that had extensive shutdowns.”

Amco’s Flannery described how the start of the COVID crush affected resin suppliers. “When COVID-19 hit in March of 2020,” he said, “nobody knew what was going to happen. The biggest concern from a supply standpoint was that the suppliers were going to go into  the summer, and they were afraid if the whole economy shut down that they were going to have inventory that they couldn’t sell. So they destocked or they dramatically cut production.” Then, at the start of the summer, suppliers were shocked by the unexpected: demand surged rather than tanking.

the summer, and they were afraid if the whole economy shut down that they were going to have inventory that they couldn’t sell. So they destocked or they dramatically cut production.” Then, at the start of the summer, suppliers were shocked by the unexpected: demand surged rather than tanking.

The pandemic caused a surge in demand for healthcare-oriented products such as ventilators, PPE and coronavirus test kits. But the demand surge was much more widespread than this; nervous citizens began buying up all sorts of consumer-quantity, individually wrapped household supplies. “All of a sudden you got a huge demand,” said Flannery, “a surge in demand for stuff like toilet paper and therefore a surge in demand for the film to wrap the toilet paper. We also saw demand for cleaning supplies skyrocket. These use a lot of polyethylene and polypropylene for the packaging and for the sprayers and other parts – and PET too. Anybody who could blow mold a bottle for any kind of cleaning supply or sanitizer of any kind, they could not make bottles fast  enough.”

enough.”

Then, with the pandemic hobbling activities and travel, home-bound Americans began a consumables and home improvement buying spree that spurred US manufacturers and upped traffic along the global trade routes. As Columbus of DELMIAWorks described it, “The factor that has contributed most to resin supply chain disruption with our customers continues to be the COVID-19 pandemic as resin producers work to produce the right mix of resin categories that reflect rapidly changing market demand.”

At the start of 2021, when resin suppliers thought that the balance of demand and supply had finally evened out a bit, along came unprecedented winter storms. The calamitous deep freeze in Texas crippled petrochemical plants, creating an even greater supply shortage. “The Uri freeze in Texas and Louisiana just decimated the supply chain for the petrochemical side,” said Flannery. “It would be like taking a hurricane that went over all of Texas and half of Louisiana in one fell swoop. We had never seen anything like that before.” And resin was once again in short supply.

“The 2021 winter storm that hit Texas was the beginning of the worst of our problems,” said Christensen. “One of the main resins we use is made in  Texas, and it backed up production for one of our key molding customers. We were accustomed to running our presses 24/7 and there was a period of time we didn’t have enough resin to run every weekend or all three shifts.” DELMIAWorks saw the same impact. “The 2021 winter storm in Texas initially had a significant impact on resin supply for our customers,” Columbus said. “Today, they’ve recovered from those shortages; it took months to catch up, however.”

Texas, and it backed up production for one of our key molding customers. We were accustomed to running our presses 24/7 and there was a period of time we didn’t have enough resin to run every weekend or all three shifts.” DELMIAWorks saw the same impact. “The 2021 winter storm in Texas initially had a significant impact on resin supply for our customers,” Columbus said. “Today, they’ve recovered from those shortages; it took months to catch up, however.”

After that, the still surging import traffic flow was hit by a whammy when cargo ships were stalled or re-routed after the cargo ship Ever Given wedged itself in the Suez Canal. Meanwhile, the US buying spree continued, and the incoming goods and materials, on ships that were finally able to navigate the Suez Canal, began overwhelming US ports, rail transport and trucking, all of which also impact the import and delivery of resin to manufacturers.

The Resin Supply Forecast

From the processor perspective at Garner Industries, the current resin supply picture still shows high prices and long lead times. “We’ve experienced price increases on every resin we buy,” said Christensen. “Supply chain was very stressed on our key resins, but more recently it has been improving. Leads times and availability still are not where they were pre-COVID. And driver shortages have been a real issue.”

The view from DELMIAWorks is similar. “Processors are holding excess resin inventory as a hedge against price increases, the threat of the hurricane season reducing supply and supply chain disruptions,” said Columbus. He noted that imports have traditionally been the relief valve for fulfilling excess demand and helping keep prices low but that exceptionally long shipping delays, massive increases in shipping freight volume and higher prices, including rising port-related costs, can add as much as 35 cents per lb. to resin costs. “Record shipment delays in the L.A./Long Beach and other west coast ports further motivate processors to hoard inventories,” said Columbus.

Flannery described the current scenario from Amco’s vantage point. “As of October, the commodity side, which includes the polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene business, was affected again because of Hurricane Ida. That put a dent in supplies for all of those. There were more force majeures that month and the industry is kind of slow to recover.” The future, said Flannery, is difficult to forecast, especially with the remainder of hurricane season stretching until the end of October. “Hurricane season,” Columbus agreed, “is a factor motivating many processors to hoard inventory today – they’re holding their breath, hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.”

“The continuing problem,” said Flannery, “is that all of these problems also affect other things that go into the resin.” While for the main ingredients the refineries may be able to get up and running, for some of the ingredients needed for special formulas the plants are still facing slowdowns and other issues. That will create shortages for specific resin grades because the co-monomers, for example, are not available. Bottom line? “There are so many moving parts. It is hard to keep track of what is worse off versus what is not as bad off at any given time.”

Columbus echoed the sentiment. “It’s challenging for resin producers to get forecasts right because the market conditions are changing so fast,” he said. “Many of them rely on advanced supply chain planning and management concepts, including collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPFR), and sales and operations planning (S&OP) with their largest processor customers.” In such an unstable environment, manufacturers must use every technique and tool available to keep their resin inventories at the needed levels and to keep their supply chains moving as smoothly and predictably as possible.

Advice for Managing the Resin Crunch

It is now more important than ever for plastics processors to understand their resin inventory levels, their upcoming jobs and the associated resin needs, and to plan and act as far ahead as they can.

“We used to be able to schedule deliveries with about a two-day lead time,” said Christensen, “and now it’s over a week. We’re seeing a shortage of bulk truck drivers on top of the limited availability of the resins we need.” Garner Industries has found that some vendors won’t commit to delivery dates at all. The company reports that order acknowledgements have been coming back with a 12/31/2021 delivery date, indicating that the vendor doesn’t know when they can deliver. “If they don’t know,” she said, “then we don’t know when we can expect the next shipment.”

Flannery offered background on the delivery snafus now regularly unfolding. “Some of the problem stems from the fact that when cargo ships come into Los Angeles or Long Beach, they usually get unloaded and the containers immediately are put on a train headed for, say, Chicago.” What has happened, though, is that so many extra containers have showed up in Chicago, for example, that there aren’t enough truck drivers to unload the trains and the trains, therefore, cannot be sent back to the west coast. To cope, the rail companies began an embargo; they would not take any more containers for some time (a week or so) to Chicago because Chicago was already full up. “And it’s not just the ports and the ships and the trains,” Flannery said, “It hits the supply chain all the way down.

Columbus had some suggestions for what manufacturers can do. “If possible,” he said, “reduce your reliance on imports – as challenging as that can be – since ports continue to be backlogged, and the per pound surcharges for ocean freight will most likely go up before they come back down.” Another option: consider how you can create a buying consortium with other processors in your industry area to bid on bulk resin buys competitively. “That’s what processors across the Midwest are doing today to gain access to resins they need,” Columbus said. “With the resin producers, you have direct buying relationships, so see if you can get more products under allocation by entering into a collaborative forecasting agreement.” He also suggested trying to motivate resin producers to provide more allocation for needed higher-margin products while processors share the price gain by paying slightly more per pound. That strategy, he said, is working for automotive manufacturers when it comes to electronics components.

Christensen described how Garner Industries is coping. “We’ve found that you must keep on top of inventory constantly and ‘order early and often,’ ” she said. “Don’t guess when a silo is going to be empty. Also, constantly ask vendors what their lead times are because lead times are always changing. We’ve had some items that used to have a three-week lead time that now require seven weeks.”

“The only thing you can do,” according to Flannery, “is get your orders in early. Processors, and especially custom molders, are going to have to push their customers to place orders way ahead of time. Basically, it’s all about the lead time.” There is little that processors can do in light of the threat of hurricanes in the Gulf Coast, but in the case of imported resin or extremely long lead-time resin, Flannery advised processors to build in buffers and focus on doing the best planning possible, and to cultivate good partnerships and communications with resin suppliers.

Flannery went on to advise that processors consider using resin alternatives and asking customers to approve multiple alternative options whenever possible, and to turn to trusted suppliers for guidance on this. “As a distributor, the first thing we ask processors to do is check first with us because we usually have an alternative. We ask processors to work with our technical team, describe the application, explain why they are using whatever resin they are using, and then let us respond from the business and technical side.” In addition to getting expert resin advice, this way processors know that any resin alternatives proposed are available in the short term and in the long term, too. “Choosing a long-term alternative would be better,” said Flannery, “especially for the next 18-24 months because it feels like the resin supply challenges are not going to change quickly.”

Flannery recommended taking the current environment as an impetus to draft supply agreements with suppliers, covering a term of 24 to 36 months. He noted that processors who are ready to place orders if spot opportunities arise can sometimes snag a good deal. “There are always times,” he said, “when a processor has a customer that cancels an order and, all of a sudden, we have extra resin due to that lost job.” He cited the example of resin buyers who were producing highly specialized COVID test kits. The had committed to purchasing resins and then those test kits didn’t take off, and production halted. “We had commitments for resin coming in, so now if that customer didn’t want it, we could sell it to our other customers. Don’t be hemming and hawing,” he urged. “If somebody makes you an offer and it is something that you really need, you should pull the trigger.”