by Liz Stevens, writer, Plastics Business

Per OSHA, the Hazard Communication Standard (HCS or Haz-Com) requires chemical manufacturers, distributors or importers to provide safety data sheets (SDSs) to communicate the hazards of hazardous chemical products. Denese Deeds and Chandra Gioiello, certified industrial hygienists and registered safety data sheet and label authors with IHSC, LLC. of Shelton, Connecticut, discussed the ins and outs of safety data sheets, including six key ways in which manufacturers can use safety data sheets within their facilities.

Understand the differences in international rules

Dealing with SDSs supplied by international sources can be challenging because of differences in how nations have adopted classification and labeling rules and due to variations in mandatory classifications. Chandra Gioiello explained that the US is aligned with Revision 3 of the GHS, the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals. Since countries from which US manufacturers obtain materials may be aligned with Revision 3 or with a more recent revision, understanding the differences between revisions is important.

The differences can be significant. “A huge difference between Revision 3 and later revisions has to do with aerosols,” Gioiello said. “In Revision 3 and earlier, all aerosols also are considered compressed gases. But in Revision 4, the GHS was reworded so that aerosols are a separate thing, no longer considered compressed gases.” On a safety data sheet for an aerosol product from Europe, there may be no notation of compressed gas, but in the US this product is considered a compressed gas.

Mandatory classifications also may differ. Europe, for example, has published mandatory classifications that do not align with US classification data, so a classification that is mandatory elsewhere may not apply in the US. “Conversely,” said Gioiello, “we in the US require OSHA-identified carcinogens to be classified as such. That doesn’t apply anywhere else, so something might come to the US that contains an OSHA-defined carcinogen but that is not classified as that on the SDS because the originating country doesn’t recognize OSHA carcinogens.”

A manufacturer who receives a non-compliant SDS from an international source can request that the supplier send a compliant SDS or can create one themselves. “An importer,” Gioiello said, “is the responsible party for the incoming chemical, meaning that the importer must generate a US-compliant safety data sheet if one was not obtained from the supplier.”

Maintain a list of hazardous chemicals

Denese Deeds discussed a manufacturer’s list of hazardous chemicals, which must be kept in a facility as an OSHA requirement. The Haz-Com Standard calls for a list of hazardous chemicals, a written hazard communication program, labeling of all hazardous chemicals and safety data sheets that are accessible by employees.

Denese Deeds discussed a manufacturer’s list of hazardous chemicals, which must be kept in a facility as an OSHA requirement. The Haz-Com Standard calls for a list of hazardous chemicals, a written hazard communication program, labeling of all hazardous chemicals and safety data sheets that are accessible by employees.

“The list of hazardous chemicals often is overlooked,” said Deeds. “Make sure that it is kept up to date. If you have chemicals, anything that is imported, anything that is manufactured in the facility and all of the purchased chemicals that are hazardous have to be on the list.” A list can cover the whole plant or be created for each department. There are software services to maintain lists electronically, or a manufacturer can maintain a list digitally and print a hard copy. There also are online cataloging system services to maintain hazardous chemicals lists, to print lists and to provide access to safety data sheets.

Spot substandard data sheets

Not all SDS are created equally… it’s important for manufacturers to know how to spot a sketchy SDS and their options if one is received. Gioiello pointed to clues, such as a SDS that lists no hazardous components yet describes the material as a carcinogen, or a SDS with significant classifications but no supporting explanation or data. A big tipoff: an SDS with inconsistencies, such as a declaration that there are no eye or skin hazards yet having first aid recommendations for those same hazards.

Another way to spot a substandard SDS is via the creation/revision date. “If a safety data sheet is more than five years old,” said Gioiello, “I would ask for an updated one.” Some older SDSs are legitimate, however, because if a product is discontinued, there is no OSHA requirement to update the safety data sheet. But if an SDS in the old MSDS format has a recent revision date, it is not a reliable document.

If manufacturers receive a questionable SDS, they can ask questions. If the supplier’s SDS does not explain why the chemical is classified the way it is, ask. “You also can ask suppliers if they have test data,” said Gioiello. Sometimes test data – which suppliers should agree to provide – will explain why a product has been classified in a seemingly incorrect way. If a manufacturer remains concerned about a questionable SDS or classification, one option is to ask for a less hazardous version of the product.

“Sometimes suppliers have a more dilute version or an alternative product,” said Gioiello. Another option is to request a compliant safety data sheet. If an SDS inaccurately represents the product’s hazards, the SDS is not compliant and a manufacturer may ask for an updated one. If the supplier will not produce one, it may be time to find another supplier with a similar chemical or an alternative chemical.

Train employees on chemical hazards

“OSHA requires that manufacturers train workers on the hazards of the chemicals that they work with,” Deeds said. “That was the main intention of the original Haz-Com Standard – to let people know about the hazards to which they are exposed. The safety data sheet is a great tool for doing training.”

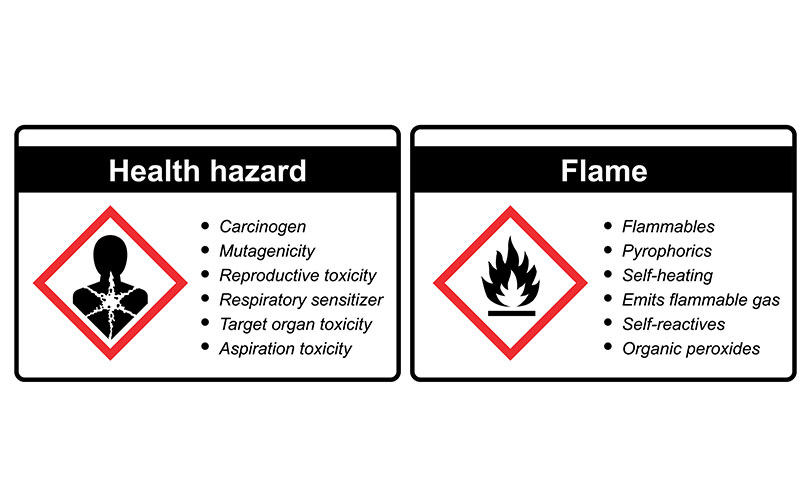

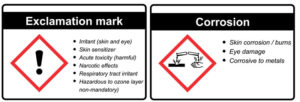

While some manufacturers may believe that it is sufficient to show employees a video about haz-com as training, Deeds says otherwise. “Manufacturers are required to train workers on the actual hazards they are exposed to,” she explained, “not just generic hazards. They can use safety data sheets to organize their hazardous chemicals by classification and that way, after covering the basics in training, they can give examples of what corrosive chemicals the employees will handle, what sensitizing chemicals are being handled and which ones are flammable.”

Use caution when converting to in-house labeling

Problems can arise when manufacturers convert GHS labeling into in-house labeling, and there are issues to watch out for when creating labels for internationally sourced materials. As with the variations in GHS revisions that can lead to mismatches or confusion, there are differences in the labeling systems available for manufacturers – many of which do not provide a one-to-one GHS conversion.

As such, it is important to check that an in-house labeling system is compatible with GHS-generated data. “We recommend that clients transition to a GHS-based in-house system,” said Gioiello, “because then it is easy to convert GHS information into in-house labeling.” Using the GHS for in-house labeling also means that plant operators only have to train workers on one system and a GHS-based system used for labeling reinforces the underlying GHS facts and warnings.

Identify alternatives and substitutes

Deeds explained some of the best uses of safety data sheets, beginning with using them to identify safer alternative materials and to avoid making poor choices of substitutes.

“The first thing is to consider what you are most concerned about,” said Deeds. “Are you worried about chronic health risks? Do you have chemical workers who have become sensitized to a chemical substance so that you need to find an alternative? Are you are dealing with environmental impacts?”

Other factors may lead manufacturers to seek alternative materials, such as state requirements that a plant not emit VOCs. Company policies may proscribe certain chemicals or call for a focus on sustainability. Before beginning the search for an alternative, confirm that the hazard information for the “problem” material is accurate. Make sure that the incoming SDS is correct and complete to avoid being thrown off by a misclassification.

Deeds advised reviewing the whole picture for a substitute material: “One thing to keep in mind when identifying or selecting substitutions is to avoid making regrettable substitutions.”

“Oftentimes plants focus on a single hazard issue, like flammability, and decide to switch to a chlorinated solvent alternative because it is not flammable, thinking this will eliminate the hazard. But the chlorinated solvent introduces carcinogenicity and also introduces serious concerns about water contamination and hazardous waste.” To avoid introducing new issues while aiming to eliminate a problem material, review the alternatives for their own spectrum of hazards and impacts.

As for environmental effects, things that are viewed as safe today may not be viewed as safe in the future. “We had that experience with PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), and now it is PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid),” said Deeds, “Those chemicals are extremely persistent in the environment, and now we have concerns about them.” Deeds advised manufacturers to be as forward-thinking as possible to prevent choosing substitutes that may prove to be regrettable.

Denese Deeds is a senior consultant and president of IHSC, LLC. She has more than 40 years of experience in the practice of industrial hygiene and specifically in hazard communication. She can be reached at d.deeds@ih-sc.com.

Chandra Gioiello is a senior consultant and vice president of IHSC, LLC. She has 15 years of experience focusing mainly on international regulatory compliance and hazard communication. She can be reached at c.gioiello@ih-sc.com.