by Liz Stevens, contributing writer, Plastics Business

Editor’s Note: This article was drafted based on a panel discussion at the MAPP Benchmarking & Best Practices Conference, which was held virtually in October 2020. The strategies detailed here are only a small portion of the content shared. For more information, visit www.mappinc.com.

Plastics processors are seeing more customers using supply agreements to document their business relationships. These agreements can be long, complicated documents full of clauses, provisions and legalese. What’s the best approach to dealing with these: a) puzzling through the terminology and implications until one’s head explodes, b) FedExing the agreements off to a lawyer for a pricey consultation, or c) closing one’s eyes, signing on the dotted line and hoping for the best?

Alan Rothenbuecher, general counsel for the MAPP organization and a partner at Benesch, a nationwide law firm, suggests d) learning about some of the basics in a standard agreement and turning to legal help for the squirrely stuff. He advises against c) signing blindly and crossing one’s fingers, even though that is what many plastics manufacturers feel cowed into doing.

Rothenbuecher, an expert in negotiating customer supply agreements who leads his law firm’s plastic industry service line, used a recent webinar to share tips for understanding agreements and negotiating the details so that manufacturers get a fair shake from customers. He also asked a panel of plastics molding executives to give real-world examples of how they successfully negotiated their supply agreements.

In the supply agreements that are increasingly being used by customers, Rothenbuecher sees a trend: “Most of the agreements are very one-sided; they favor the customer,” he said. “Yet molders readily sign the agreements, thinking they have no other choice.” But in addition to customers drafting supply agreements more often, they are also becoming more receptive to negotiating the terms of the contracts, allowing manufacturers to ask for provisions that are fair and equitable. As in any negotiation, the bargaining can only begin if one of the parties request it. Rothenbuecher’s advice is to expect pushback, and forge ahead anyway. “When you ask for changes,” he said, “you hear responses like, ‘Well, everyone else has signed it.’ ‘You are the first person I ever heard of to push back on this.’ ‘Oh, I need to get approval for this.’” His advice: do not cave. “Ask for changes. Customers will listen and negotiate. You won’t get all, but you will get many of your requested changes.”

Why engage in the negotiation? “If you leave the agreement as-is, you assume all the risk,” said Rothenbuecher. “You assume the risk for mis-designing a part even if you didn’t design the part. You are stuck with damages to the parts while in transit, even though you didn’t pick the shipping company. You agree to pay all costs for a defect, even if the defect is caused by the customer installing the part incorrectly.” Those details and that fine print can kill you. Manufacturers need to be ready to negotiate it and change it.

When the fine print only includes one-way indemnification provisions, for example, Rothenbuecher is adamant that processors should not get unfairly stuck for any patent infringement. “If you didn’t design it,” he said, “they are still going to ask you to indemnify for an infringement of a patent.” That is not fair, and a manufacturer should negotiate for a change in this type of provision.

On the flip side of patent infringement is assignment of all inventions. If a molder has a process-oriented invention that can be applicable for products beyond those produced merely for one customer, the invention is worth more than just its practical value to the manufacturer. Rothenbuecher explained that this is particularly significant for plant owners who might sell their companies in the future. “If you are trying to sell your company, a buyer always wants to see if there are things of value [such as inventions] in your company,” he said. It is therefore important to make sure that ownership of inventions is retained by the inventor/manufacturer. If an invention is created for the manufacturing process and it happens to be on the watch list of a customer who has that “assignment of all inventions” provision in their supply agreement, this will assign ownership of the invention to the customer, as opposed to the rightful manufacturer/inventor. “You can’t let them do that,” said Rothenbuecher. “If it is something that can be used for other products, unrelated to that one customer’s product, you need to push back on that assignment of all inventions provision.”

In the case of customers that include a request for financial statements in their supply agreement, Rothenbuecher sees irony. “The irony here,” he said, “is they want to see if you are going to do well; the problem is it’s most of them that aren’t doing well. The easiest way to push back on that is to say, ‘You show me yours, I’ll show you mine,’ and you will see how quickly customers will strike that provision from the agreement.”

Regarding the design of parts and warranties, Rothenbuecher had several words of advice. “If you are not designing the part,” he said, “you need to limit your warranties.” Plastics molders should only specify that they are making a product “to spec” and that it will be good workmanship. “Get rid of the warranty for merchantability,” said Rothenbuecher, “and get rid of the warranty for fitness for a particular purpose.”

Lately, Rothenbuecher has seen many clauses regarding demand for product after the program concludes, often with a five-year “after conclusion” term, with no provision for price increases over the years. “There is no way that original price should still hold for those parts,” he said. “Remember, when you initially price the product, you are assuming a certain amount of turnover with respect to the products – so many cycles, so many products – and you based your cost on that. If the product is a spare part and the mold has been put on the sideline, you have got to put it in the machine to make only a few more spare parts. To do that, there is a significant cost increase and customers are beginning to understand that there also needs to be a price adjustment put forth in the agreement.”

The COVID pandemic has made force majeure – unforeseeable circumstances that prevent someone from fulfilling a contract – a hot issue in legal documents. For protection, supply agreements should include force majeure clauses that cover both the customer and the manufacturer. “It is most important to consider that if a customer declares a force majeure event,” said Rothenbuecher, “and it lasts a certain period of time, you need to have in your supply agreement a term that says you can walk away from the contract after a specified amount of time. You shouldn’t be waiting on the sideline for 60 or 90 days if there are other customers you can get work from and you can use those idled presses for that work.” Once again, fairness is the key. “Every force majeure clause allows the customer to say they have the ability to do that. What’s unfair about you asking for the same thing?”

Experience from the trenches

Rothenbuecher turned to three industry executives for real-world examples of dealing with supply agreements. Tammy Barras is president of Westec Plastics Corporation in Livermore, California, a company that specializes in tight tolerance mold manufacturing and production. Jim Kepler is president of Intertech Plastics, a custom injection molding company based in Denver. And Tom Nagler is CEO of Natech Plastics, a custom molding manufacturer located in Ronkonkoma, New York.

When asked whether they embrace supply agreements or hate them, the response was unanimous: these executives embrace them. “We embrace them,” said Kepler. “From our perspective, it allows us an opportunity to build a closer and stronger relationship with our customers. It also takes a lot of the gray out of the difficult conversations surrounding pricing, returns, any type of safety stocks, things like that that can be difficult waters to navigate. It allows us to define those together, so we embrace them.”

Barras agreed. “Westec works really hard with our customers to ensure that we are all on the same page,” she said. “It is much easier to sort out the gray at the beginning of the relationship rather than having to figure out how you fix it three years in. Supply agreements are a benefit to both the customer and us as molders.”

Rothenbuecher inquired about supply agreement experiences that have been particularly challenging for the processors. Kepler mentioned an experience with a long-term customer that made a strong impression. Spurred by changes at the corporate level, the customer presented a new agreement that was one-sided and included language that was challenging to understand in light of Intertech’s long history with that customer. “We flew out and met with the legal team and the purchasing department of the company,” said Kepler. “During a leadership class I attended at West Point, I heard a phrase that I will never forget: ‘It’s harder to hate in person.’ When we got face-to-face with the customer and talked about the relationship that we had built over decades, we were able to come to language that was very fair and equitable; but it did take a couple face-to-face meetings.”

The value of building relationships surfaced again when Nagler described how Natech aligns its interests with those of its customers at the start of agreement negotiations. “I like the concept of relational contracts,” said Nagler. “The idea is that you spend time up front establishing what the shared vision for the relationship is, and what guiding principles will set the framework for the relationship and the contract.” Instead of focusing on trying to outline every circumstance that might occur, if a framework of values is created – like honesty or integrity or reciprocity – this establishes a mechanism to use when the inevitable does occur. “I love that word – reciprocity – because if the client is willing to do it, it means that they are a willing partner and that they believe in principles and values,” he said. “If they are unwilling to do it, they are sending the opposite signal.”

When Rothenbuecher asked about trends emerging for supply agreements, Kepler noted that he has seen an increase in supply agreements being drawn up, especially with the impact of COVID on industry. “We are also seeing these agreements becoming more complicated,” Kepler said. “We see a trend of customers including quality agreements, along with supplier agreements, that define how parts are being measured, critical dimensional specifications, gauge R&R requirements, very detailed language defining expectations, controls and countermeasures. These make for long or complicated review sessions with our team and include language that I believe calls for some legal counsel.”

Kepler said that, for his company’s smaller customers, Intertech will offer to present its own stock agreement, which can speed up the supply agreement approval process. “With larger accounts – the more sophisticated customers – they often already have stock language in place,” he said. “In those circumstances, we ask that they prepare the first draft. That allows us an understanding of what is important to them. It also prevents a lot of wasted time and resources, and legal expenses, for us to draft an agreement that doesn’t fit their standard template or address their concerns.”

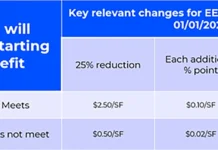

Rothenbuecher inquired about how the companies deal with language surrounding price changes. Kepler stated that Intertech calls for pricing to be re-evaluated, at a minimum, on a quarterly basis. Intertech also includes, as stock language, a 5% threshold on pricing increases or decreases. “And for customers that utilize commodity grade resins,” said Kepler, “such as polypropylenes or HDPs, where we supply high volume packaging or industrial products, we like to tie pricing to chemical data indices.” Chemical data index subscriptions are a significant investment for Intertech, but for a company that purchases over $6M in raw materials, the return on investment for the subscription is substantial. “In the past, when we did not set up agreements in this way to follow an index quarterly, we would leave $250,000 to $500,000 on the table by not passing along material increases in a timely manner. For us, specifying the use of a CDI index with our high-volume customers is a must.”

At Westec, Barras asks for a regular review for pricing since labor costs in California are higher than in other parts of the country. “With the majority of our customers,” she said, “we do an annual review, but we leave an opening so that if we see a change of plus or minus 10% in labor or in packaging or in raw materials, we reserve the right to at least review the pricing with the customer. That way they can work with us so that we don’t lose our margins and they don’t lose theirs, but we have to work together.”

Rothenbuecher asked the executives to describe their companies’ must-haves in a supply agreement – the draw-a-line-in-the-sand provisions or requirements. Barras explained what Westec sees as nonnegotiable. “There are two main points that I would like to have very clear. One is that Westec does not design parts; we cannot be responsible for the functionality of products. We follow the specs on the print, and we make a part from that print. We can’t be responsible if they install it or use it or store it improperly; those things cannot be Westec’s liability because we have no control over that.” For Westec, the other must have is a set timeframe for acceptance of a product. “A lot of customers want 90 days or six months to look at a return and to reject the product,” she said. “But that doesn’t work for us because we are still making the product. If they discover something in six months that is an issue, we have been building product for those six months. Our acceptance timeline is 20 days; that gives them time to inspects and it helps guarantee that we are not continuing to manufacture parts that will be rejected.”

Nagler noted that his company wants protection for its custom design work. “We are engineering-heavy on the front end,” said Nagler, “and we find that to be a profitable and enjoyable part of our business. In that regard, we want to be really clear that once we hand a design to a customer, that it is their property. If they own the intellectual property that we created for them, then they also own the risk.” Kepler’s response echoed that of Barras. “What is important to us is having language surrounding defects and non-conforming products,” he said. “We produce high cavitation products in high volumes, so we limit the time in which a customer must acknowledge the inspection acceptance of product to 30 days or less. If the buyer fails to signal acceptance or make such a rejection, that is deemed to constitute acceptance of that product.” That timeframe allows Intertech to minimize its risk and avoid producing hundreds of thousands or even millions of additional parts before receiving word of a problem or defect.

To wrap up the discussion, Rothenbuecher asked the executives to share a message or theme with other executives in the industry. Kepler urged industry executives to seek legal counsel on supply agreements. “Other advice I would give is don’t be afraid to ask your customers about their intent in adding a clause to an agreement. Just because the language is in their contract doesn’t mean it isn’t just stock language where they might be trying to cover a broad spectrum of suppliers. The language might not be applicable to you.” Kepler also suggested scanning agreements for important provisions hiding amid the fine print. “Look for buried language. We found, for example, in clauses for supplier modifications that there is language specifying that the agreement can be terminated if you do not agree to modifications that are requested by the customer.” Kepler finished up with a word to the wise. “And, finally, I would say you’ve got to pick your battles. Sometimes we roll with the small stuff. You can’t make every single clause a battle or you will never get through these agreements, so pick your battles and choose the language that is important to your company.”

Nagler offered two distinct points. “I think the starting point should be that we have a lot of value to deliver,” he explained. “Therefore, if you receive an agreement that is adversarial, the first question to ask is, ‘What is your opportunity cost?’ The opportunity cost of getting swamped in that negotiation might be very high.” Nagler’s second piece of advice is to get help when needed. “If I need a doctor, I go to the doctor; I don’t diagnose myself. If I am negotiating an agreement, I get legal help, and that happens to be from Alan Rothenbuecher.” Nagler also relies on his trusted team for support. “Two reasons I need help internally: one is because I might miss something and, two; I can get wrapped up in negotiating a specific agreement clause. Like Jim pointed out, you need to be dialed back in terms of choosing the battles that need to be fought, so I use my internal team for both of those reasons – to catch things I might overlook and to give me perspective on issues.”

Barras agreed with her colleagues that reaching out for legal support is definitely worthwhile. And for her, working through issues is a key objective. “Bottom line,” she said, “is you have to learn how to work with your customers for a mutually beneficial relationship. Because that is everybody’s hope, to get the business, to continue the business and to grow the business. If you can build that partnership when the business relationship is just starting with a mutually agreed upon agreement, you can only go up from there. Just work together, keep it respectful and build that partnership.”

When it comes to negotiating supply agreements, industry leaders will improve their success rate if they learn about the basics of a standard agreement, ask for needed changes to keep the agreement fair and equitable, and turn to legal help for the tough stuff.