by Liz Stevens, contributing writer, Plastics Business

Creating and conducting a training program is hard work, but it is worth the investment – because when employees gain knowledge, companies gain valuable expertise. However, creating a methodology that easily explains the program and the benefits it offers can be challenging.

Makuta Technics and Engineered Profiles are two vastly different manufacturers that have created training programs for the benefit of their companies and for the benefit of their associates. We spoke with Stu Kaplan, president of Makuta, and with Adam Wachter and Paul Cunningham, CFO and training manager, respectively, at Engineered Profiles, to learn about the training programs at both companies.

Engineered Profiles: Organized training schedule eases employee advancement

Engineered Profiles, LLC, Columbus, Ohio, has been providing leading-edge plastic extrusion solutions to a wide array of industries for over 70 years. The company runs on a 24/7 schedule with about 250 full-time employees. It has 45 main extrusion lines, three production buildings and one fabrication cell. With twin and single screw extruders, Engineered Profiles works with PVC, PE and PVC wood composite, PP, PE, ABS, PS, PC and Nylon.

In 2015, Paul Cunningham was plant manager at Engineered Profiles, having worked his way up over the years from his start as an operator. Training there had been going on for decades in a very casual manner, with only sporadic attempts to create a more cohesive approach.

“There wasn’t really anything formal,” explained Cunningham. “Our means of training people was to give them some paperwork when they were hired, have them work with different operators every day and tell them that when they felt ready they could take a test to see if they could become an operator.”

That approach wasn’t as effective as needed. “We were having a lot of trouble keeping operators,” said Cunningham, “so we felt that formalizing a plan – a career path – would help us get and keep people. In 2015, we formalized a program, and I took the training manager role.”

CFO Adam Wachter explained that creating the training program and resulting training matrix for Engineered Profiles employees was tied to providing employees clear expectations as it related to pay increases and a career path. “Our entry level operator pay is $13,” he said, “and our aim was to get people to a higher wage more quickly. Our goal within six months was to get them to $15 an hour.” Cunningham explained further: “We wanted to accelerate that path because, in the past, there were operators who had not advanced for a couple of years, and they felt stagnant,” he said. “They didn’t have a clear understanding of how to move up.” With the new training matrix, employees would know from the start where they could advance, and how to get there.

In designing training to facilitate employee advancement, Cunningham first focused on extrusion operators. He recruited the plant’s experienced operators, and together they hashed out a training path. “We wanted to standardize the information that everybody was hearing,” he said. Previously, employees were being taught different things, depending upon which person was teaching them. After creating the entry-level path, the group then detailed the knowledge requirements for an extrusion operator to advance to senior operator, and so on, so employees knew what it took to obtain positions in the top bracket.

Cunningham and Wachter described only two significant challenges that they faced in implementing and rolling out their program – working with reluctant veteran employees and sorting out how to schedule classes in a 24/7 work environment.

Cunningham explained that some employees had been with the company for 10, 15 and even 20 years. The company’s desire for consistent training meant that even veteran operators needed to go through entry level operator training along with the less seasoned employees and the new hires. When veteran employees initially expressed reluctance, Cunningham understood.

“I told our experienced operators that they had probably forgotten more about plastic than I will ever be able to teach them,” he explained. “But once I explained to people what we were trying to accomplish – that when new people came in, we would all know how they were taught – it made sense to them.”

Wachter pointed out that the veterans were given a lot of leeway to take classes. “We gave everyone a year or two to get back to their level on the training matrix,” he said. “In the first year, it was voluntary – we told them classes were available and they could attend if they wanted.” In the second year of the training program, veteran employees were urged to take the classes and complete the tasks required for anyone who had advanced to their pay grade. “We pushed a little,” Cunningham admitted. “I had to poke and prod a few people, but overall it was a pretty easy transition.”

Then there was the issue of scheduling for classroom training. “When we originally started, we were going to take a couple of operators off the floor during their shifts and have them come in and do the classes,” said Cunningham. “We realized pretty fast that wasn’t going to work.” The company’s solution was to present courses on the employees’ days off, and to pay them overtime to take the daytime classes.

The 24/7 operating schedule presented the next hurdle, said Cunningham, “because then we had people say, ‘Well, I’m on night shift. Why are you making me come to a class on days?’ ” Once again, the training program was adapted. “Now I do some classes in the evening to try to help with that,” he explained.

The company’s willingness to fine-tune the training to accommodate employees sent a signal to all of its workforce. “We’ve adapted to what we feel has helped the team, to make the training as convenient as we possibly can for them,” Cunningham said. “And, that has been well received because they know that we are willing to do what we need to do to help them.”

At Engineered Profiles, training now is an organized process that includes classroom time with Cunningham teaching the operators, some computer-based classes delivered via the Cornerstone LMS and hands-on training. “I think the absolute best change to the program that we’ve made over time is the way we do hands-on training now,” said Cunningham. “When we first rolled it out, I would have new associates for a week in training.” New hires then would return to their regular shift, and a shift-mate would do hands-on training to reinforce what Cunningham had taught in the classroom. “We were having a lot of disconnect with that,” he said, “whether it be line needs, coverage, not having enough people or having to move people around. It was inconsistent.”

The company decided to choose one hands-on training person. Now, when Cunningham finishes the entry-level training class, Greg Marcum, the company’s hands-on trainer, spends two to three weeks with the newly trained operators. He walks them through the processes of their jobs, including how to set up a line, start up a line, run a line and tear it down. That is repeated every day, giving the new employees solid practice in the processes that they need to know to do their jobs. “That,” said Cunningham, “has been the biggest positive for us through all of the training, because I think it helps them feel confident and ready to do the job when they go out on the floor.”

Makuta: Pay-for-knowledge system rewards ambition

Makuta Technics, Inc., is located in Shelbyville, Indiana, southeast of Indianapolis. Founded by Stu Kaplan in 1996, Makuta specializes in micro injection molding and micro mold tooling, producing millions of zero-defect micro plastics parts each month for customers in the medical, pharmaceutical, micro fluidics, and electronics and office automation industries. Makuta runs lean, with a workforce of 10 employees and conducts 24/7 “lights-out” manufacturing.

Stu Kaplan has had a training philosophy and methodology in place nearly from the start. A fourth-generation manufacturer, Kaplan explained that during his years in manufacturing, including “driving a forklift in a metal stamping factory when I was 8 years old,” “working on the west side of Chicago in union shops,” running a factory on the west side of Chicago (where he learned what not to do), working in Japan and marrying a woman whose family has been in manufacturing for four generations in Japan, he came across plenty of variety in training methods.

Since Makuta is a highly specialized plastics operation, Kaplan is quite selective about new hires, and oftentimes finds that prospective employees with plastics manufacturing experience do not fit well with Makuta’s unique specifications. “What we do, technically, is so different than what other people do,” explained Kaplan. “We have four-cavity molds that we carry around in our hands, as opposed to using a crane or a forklift to move them. So, handling components of our molds – they are like pieces of jewelry to us.” Once he has found a new employee who clicks with the Makuta mindset and culture, Kaplan knows that training will need to be very specific and won’t be found in a pre-planned plastics educational system.

When he started his own business, Kaplan implemented a pay-for-knowledge system to encourage employees to take control of their own advancement. The premise is simple: After agreeing upon a starting wage, new employees are told that to increase their salaries, they have to get more knowledge – whether internally through the pay-for-knowledge program or by going to school.

“The program is based on the knowledge that our people have,” Kaplan explained. “It requires increasing your knowledge over the entire time you are with Makuta.” This system involves every aspect of the company, from shipping to molding parts to facilities maintenance to purchasing and accounting.

After a period of time, usually 90 days after hiring, new employees take a test – an applied, written and oral exam – certifying that they are knowledgeable about their primary position. “At that time,” explained Kaplan, “they are free to say, ‘Okay, I’d like to make more money in another area. And, I’d like to learn something else.’ So, they may go to one of the certified people in molding and ask that person to teach them a skill set, such as single-shot or double-shot molding.”

The training – a mix of mentor-protégé discussions, videos and online classes – usually takes two to four months, and then the trainees take an applied, written and oral exam that demonstrates that they can operate the machines correctly, are knowledgeable about the materials used, know how to document the parts they are making, et cetera. “Once they pass those exams,” said Kaplan, “not only does the student get a bump in pay, but the professor who taught them gets a bump in pay. That’s the basics of it.”

Kaplan’s training premise incentivizes workers to share knowledge and get smarter. The core of the knowledge sharing at Makuta is plant operation. “The courses we have developed cover everything needed to keep the place operating,” said Kaplan. “Because of the way we operate (lights out and with few employees), that cross-training is key to our business model.” Every year, Makuta employees must re-certify in their cross-training knowledge; that is, the positions other than their primary responsibility.

Part of helping employees get smarter also includes supporting employees with internships and outside learning opportunities. “We’ve had intern programs with high school students who worked part-time for us and now have been with us six or seven years, working their way up through the pay-for-knowledge system to responsible positions at a very young age,” said Kaplan. “We’ve also provided the work schedule flexibility and financial support to help employees with external programs such as off-site plastics processing courses, the two-year certificate program at local Ivy Tech Community College with credits that are transferrable to Indiana state colleges, and even accounting certificates and MBA programs at other universities. To be effective, our pay-for-knowledge system has to be dynamic.”

Deploying a win-win training matrix

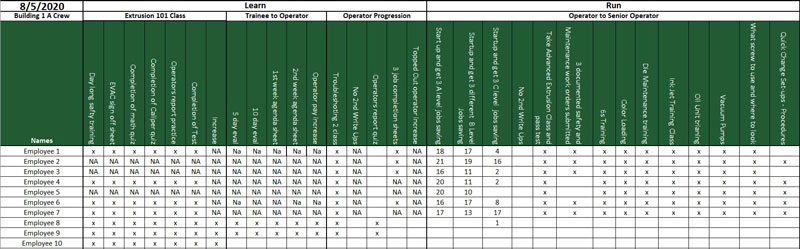

Both Engineered Profiles and Makuta Technics use a training matrix – a grid used for tracking employees and their progression through a series of training courses. The matrix can be as simple as a printed, posted chart that is updated by adding notes or check marks. Or it might be a sophisticated Excel-based workbook or learning management system-based table that is updated online and then printed and posted on a regular basis. They key factor is that it is a persistent visual presentation that lets managers and employees see, at a glance, where everyone stands on their advancement paths.

Training matrices help managers track employee training, make sure everyone gets trained consistently and on schedule, and identify progress or the lack thereof. Training matrices help employees by giving them a concrete, visible path for training and advancement, by showing opportunities to learn new skills and by highlighting the employees’ achievements.

At Makuta, due to its small employee footprint, the company needs just one matrix to manage training and track employee progress. “The management of it is really pretty simple,” said Kaplan. “There is a matrix that we keep that shows who is certified, who is re-certified. And, the information on that matrix is available to everybody.”

At Engineered Profiles’ large facility, training matrices are used extensively. “A matrix is posted for each department in the plant,” Cunningham explained, “and it’s updated at least every two weeks.” At any time, employees can walk up to the matrix to see their progress along a path and what they need to get done to reach the next level.

“One of our goals with the matrix was to take the subjectivity out of advancement,” Cunningham said. “If an employee completes all the things on the list that we say are necessary for each level, there’s no wondering if the employee can move up or not.”

Cunningham was surprised at the reaction to the posted training matrices. “Some people are more driven than others,” he said. “Some people push really hard to get through as quickly as they can. Others are comfortable going at their own pace, but they know how to move from one level to the next.”

As with the company’s training program, which initially focused on extrusion operators, Engineered Profiles also has expanded its use of training matrices. “Now the fabrication department has a matrix,” said Cunningham, “and the supply chain, too. The shipping group has a matrix. We have a matrix created for our tooling group, but we haven’t put the finishing touches on it.”

The glue that holds it all together

In talking with Stu Kaplan at Makuta and with Paul Cunningham and Adam Wachter at Engineered Profiles, the conversations kept circling back to a unifying element. Whether the subject was what to put in a training course, how to deliver the training or what technology to use to manage the program, the why, how, what and when were always dependent upon the attitude of who was involved.

Kaplan repeated again and again that people are the glue that holds a company together, and that people are the movers who make a training program (and a company) succeed. In describing any aspect of operations or training at Makuta, Kaplan stressed that “people make this place run.”

He credited his vice president, Tyler Adams, for expertly managing the training program and, in talking about the initial impetus for the company’s “pay-for-knowledge” program, he repeatedly noted that it was a group effort that was constantly evolving. At Makuta, accountability, ambition and “roll up your sleeves” commitment are not just boons found in the occasional new hire – they are the standard for employee attitude.

“At Makuta,” said Kaplan, “there’s a goal for the individual employee and for the employees collectively: ‘to make our lives better.’ As they are making their lives better, mine gets better. So, that brings us right back to the basis for the pay-for-knowledge plan.”

At Engineered Profiles, Paul Cunningham cited the enthusiasm, engagement and contributions of the employees repeatedly as the most important factors in the success of his company’s training program. Adam Wachter wrapped up our interview about the company’s training program with some thoughtful observations.

“I would say that one of the key pieces, I think, is Paul,” said Wachter. “Having someone in the role who really cares that the employees learn is important. Paul has a passion to make sure everyone is successful, and he’s involved in their whole first year by checking on them once they are out on the floor.

“We could have a great PowerPoint presentation that we give to everyone, and it would certainly not be the same,” he continued. “I think what it takes to make a great training program is someone who is really passionate about both helping the company and helping our employees to be successful.”