by Lara Copeland, contributing editor

Plastics Business

Frandsen Corporation, North Branch, Minnesota, has a family of businesses in the manufacturing and banking sectors. Each year and for each of its businesses, Frandsen creates a one-page business plan to help the companies continue to succeed. The executive leadership team spends several days together assessing what is happening internally and externally with each company and, from there, they identify what they believe to be the most important goals for each organization to work on that year.

“We focus on one or two things that will be transformative or critical in improving business and service to customers,” Amy Scheel, head of marketing at Frandsen, explained. For one of its manufacturing companies, Plastech Corporation, located in Rush City, Minnesota, the team identified scrap reduction as a critical need in 2016.

“Eight percent of our production did not pass examination and had to be scrapped,” Scheel stated. She said it wasn’t just the financial implications they had to deal with. “We knew if we could get world-class in our performance, along with hitting specifications on our productions floor, we were not only going to reduce our scrap and improve performance financially, we were going to do a better job of servicing our customers.”

The executive leadership team decided to reduce the scrap rate by 50%. “This seems pretty aggressive, but that’s why we used the Four Disciplines of Execution to help us break it down into manageable pieces called ‘battles,’ ” Scheel noted. They planned for the entire scrap reduction process to take 24 months to complete, with the first year focused on getting various teams established, designing training and curriculum, identifying what was needed for real-time monitoring and then getting those items built and implemented.

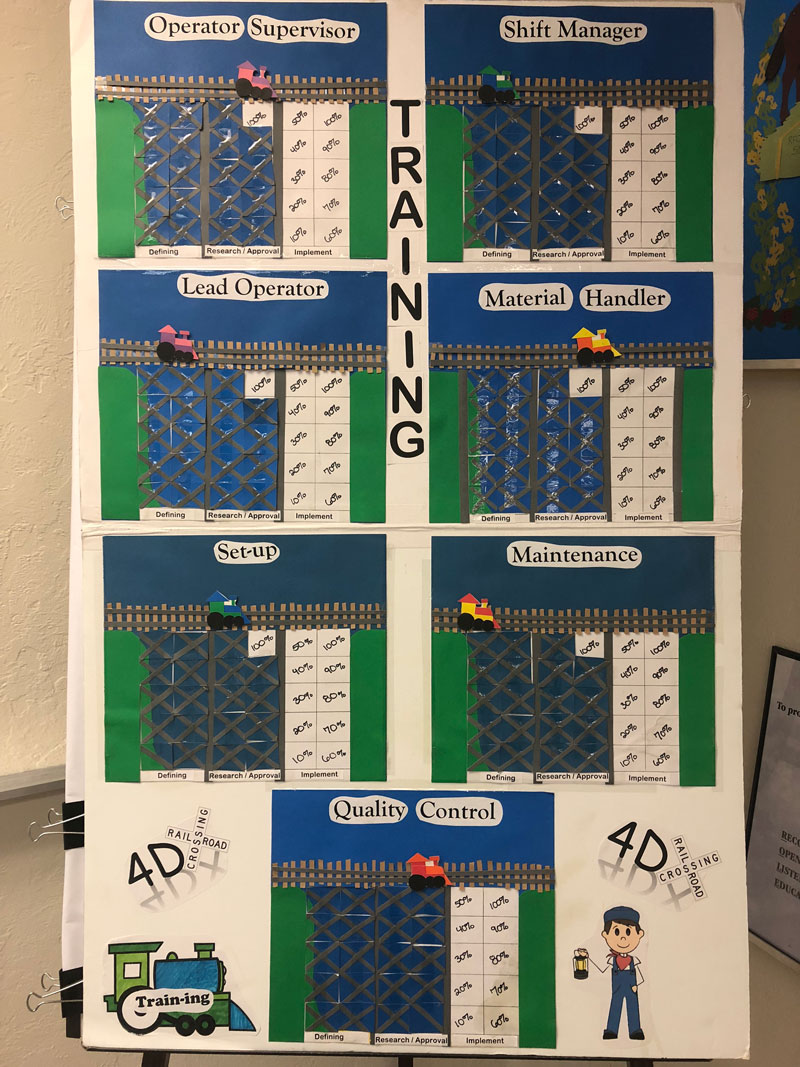

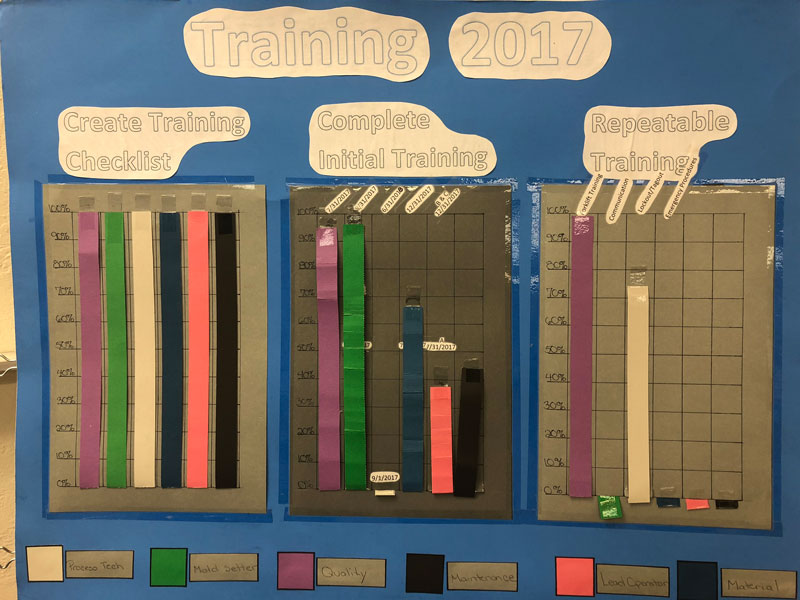

First, a team was identified and assigned to this reduction initiative. The team was made up of key roles within the organization that could contribute productively to this goal. This team then was asked to identify the battles they wanted to work on. “We asked them to think of what things they could tackle – things that would result in winning the war,” Scheel said. The team decided to work on technical staff training, in addition to monitoring and active use of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

Jerry Miller, director of operations at Plastech, said, “We realized that if we defined some curriculum training around our technical staff and trained them well, we would produce better products.” So, a team was developed, and criteria and curriculum were established for each department. “We implemented the training and then established monitoring and tracking processes to make sure that this is sustainable going forward,” he said. The training included mold process technicians, material handlers, quality technicians, supervisory staff, managers, maintenance and lead operators.

“What’s unique about this is that the team that identified the curriculum also developed the curriculum and the process for monitoring, tracking and ensuring continuous updating,” Miller added. In other words, the executive leadership team and the management team stepped aside, and staff-level employees made up the teams. With a little guidance from management, these employees led the projects and initiatives. “The people who actually do the job were the ones who developed and built this,” he said.

Plastech also reported secondary benefits from this training. “We feel that one of the best things you can do to help a new employee to become successful and to retain them over time is to provide them with good training,” said Miller. Providing trainees with the tools, support and structure they need to succeed not only helped in scrap reduction, but it also helped the company support new employees.

Miller said the second item to tackle was real-time process monitoring and active use of KPIs, so the company invested in equipping all 44 of its injection molding machines with ERP real-time process monitoring. “This was a significant investment in hardware and software to monitor and manage our injection molding machines down to the key processing parameters,” he explained. The team identified what the key processing parameters of each molding machine were to assure quality product was being made, and they purchased the equipment and put it in place on each machine.

Teams met every week to monitor the progress. “We had tracking documents and weekly commitments to follow up on action items, and we put together visual scoreboards for them on their lead and lag measures,” Scheel said. She noted that “there’s something very true about the ‘game on’ concept for people when they see the scoreboard.” She reported that the teams executed the Four Disciplines process and program on a weekly basis. Additionally, each team leader had a monthly check-in with the executive team, and the subteams presented scoreboards showing their progress and challenges on a quarterly basis to the executive leadership team.

Breaking down the main goal into smaller, more manageable parts worked well for Plastech. Miller said there were two items on the process monitoring that were crucial to the company’s scrap reduction. “The first one was developing the engineering processes for the molds, tools and parts,” he added. “We put the control limits around each one of those processes to ensure they’re up and running within the specifications of the machine and parts, and we monitored them every single shot.”

For every molded part that came out, the key processing parameters of the molding machine were monitored through IQMS real time. If a machine ran outside the control limits, the technical staff was alerted so they could perform an analysis and investigate what changed in the process before making any modifications to the molding machines. “This was key to the process,” Miller concluded.

“The second important part of the process was the reject reporting,” Miller said. In the past when the job was completed, a report would show how much scrap was made. Miller said they knew their lag measures, meaning they’d realize at the end of the run that mistakes were made. “Now we see the lead measures – what we put into place now is scrap reporting in real time.” At any given time, Miller can look at the plant floor and check the performance of all 44 machines – he can see which ones are running scrap outside the standard. “We put this plan in place, and now every two hours the machine reports scrap greater than standard.” This is communicated by email and/or text, and it alerts the managers and technical staff the machine is running outside the standard.

When a machine runs outside the set controls, staff go to the machine and complete a written corrective action response on the nature of the problem, and then they make the correction. A crossfunctional team, made up of members from various departments – such as engineering, purchasing, quality, manufacturing and other areas – reviews the corrective action responses every 24 hours. Miller explained that, when this first started, the stack of corrective actions every morning was quite high – 10 to 15 machines.

“Each time we came in thereafter, our scrap was getting reduced,” he continued. “We went from 40% to 30 to 20 to 15 and even down to 10%, until it went all the way down to where we are today.” This was the key – getting real time lead scrap measure from the machines and operators to the technical staff and leadership, so that the problem could be identified. “Taking immediate action instead of waiting until the next run was vital to our success.”

The plan of attack was part of Plastech’s 2016 annual business plan. Toward the end of first quarter that year, teams were established and the battles kicked off. By the end of that calendar year, all training was created and the real-time monitoring was identified as a key component.

In 2017, the focus evolved. “By then we took what we built, had it established as a continuous process and then leveraged what we were getting out of real time and feeding that back into the organization through KPIs and a continuous feedback loop to the floor,” Scheel reported. “As part of that program, we established a KPI communication board for our floor so that they were aware of not only what was happening with scrap, but all the KPI and all the key things they needed to know about business and the operation.”

Today, the scrap rate is less than 4%, representing significant annual savings. Scrap and quality management gains certainly have been made, but Plastech also reports even more benefits. For one, finished goods inventory is automatically updated to the ERP system and raw material inventory consumption is tracked and validated against physical inventory counts. Furthermore, machine and tooling maintenance schedules now are based upon actual run times and cycle counts as opposed to arbitrary standard day counts. More gains have been made by using the “runs best” feature in the IQMS software. This identifies which combinations of job, machine and tool produce the highest quality and most efficient production.

While investing in process monitoring equipment and software for each of the 44 molding machines is a hefty financial outlay, it was clearly a smart one. “We realized that with the reduction of scrap, our return on investment was less than a year,” Scheel exclaimed. Miller concluded that with a 50% reduction is scrap, “our return was quick.”